Controlling the expression of implicit bias in a clinical setting is a very complex balancing act. Physicians need to rely on categorizations based on age, gender, race, and ethnicity when formulating a diagnosis. Once these biases are activated, physicians need to then “individuate” the patient, developing personalized treatment recommendations and engaging in patient-centered dialogue. It is essential to design highly customized education programs and to begin training as early as possible.

Implicit bias is a manifestation of prejudice deriving from thoughts and feelings generated outside of an individual’s conscious awareness. These automatic judgments can be especially dangerous in a clinical setting, where they may be contributing to the health care disparities often experienced by vulnerable and underserved patient populations. A new publication from the University of Arizona presents a promising approach to reducing implicit bias in medical trainees. Alliance to Advance Patient-Centered Cancer Care Investigator Dr. Jeff Stone and his colleagues developed and tested an intervention aimed at reducing the stereotyping of Hispanic patients as medically non-compliant. The term refers to a patient’s unwillingness to follow treatment recommendations or take medications as prescribed. Studies show that physician implicit bias may influence treatment recommendations: one study found that African American patients were significantly less likely to receive a recommendation for thrombolytic drugs to treat myocardial infarctions compared to their white counterparts.

Controlling the expression of implicit bias in a clinical setting is a very complex balancing act. While most physicians hold important egalitarian principles regarding the fair and patient-centered treatment of all their patients, they are often called to “stereotype,” or use group based information about patients at the same time. Physicians need to rely on categorizations based on age, gender, race, and ethnicity when formulating a diagnosis, as some diseases are more likely to occur in specific subsets of the general population. However, once these biases are activated, physicians need to then “individuate” the patient, developing personalized treatment recommendations and engaging in patient-centered dialogue that will help the patient be fully involved in all treatment decisions.

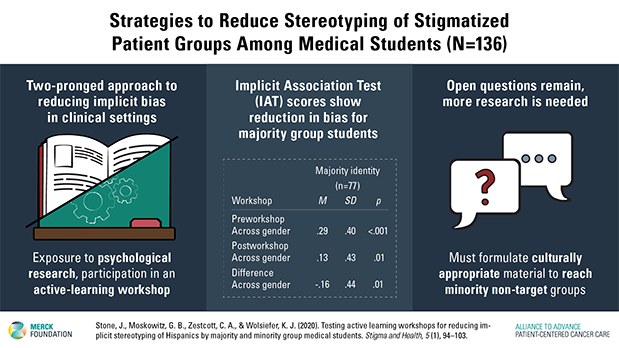

Due to these concerns, it is essential to design highly customized education programs and to begin training as early as possible. Medical students enter medical school carrying their own set of implicit biases, and their prejudices can remain the same or even increase after they start their clinical rotations (Stone et al. 2020). Dr. Stone’s intervention starts with a review of psychological theory and research into the science of implicit bias, followed by participation in a hands-on workshop designed to resemble a real-life interaction with a patient. This intervention, supported by the Alliance to Advance Patient-Centered Cancer Care, included 78 majority-group (White) participants, 16 target minority group (Hispanic, African American, and American Indian) participants, and 42 non-target minority (Asian American and foreign-born individuals from East Asia and Southeast Asia) participants. All intervention participants were medical students in the American Southwest.

Dr. Stone and his colleagues measured the degree to which the medical students exhibited implicit bias by administering the Implicit Association Test (IAT) before and after the intervention. The resulting data registered a statistically significant reduction in bias for majority-group medical students; the results were significant for white men, white women, and across genders. However, the study authors noted no significant change among minority non-target medical students, who exhibited signs of implicit bias before and after the intervention that were largely unchanged.

While the data on majority group medical students is very encouraging and speaks to the strength of the two-pronged model developed by Dr. Stone and his colleagues, the data on non-target minority students shows that more research in the development of culturally inclusive interventions is needed. It is especially crucial to develop programs that are tailored to reach medical students of Asian descent, who currently make up a significant percentage of all medical school matriculates (around 20% in 2016), with numbers projected to grow in the coming years. Reducing the expression of implicit bias in all medical students will ensure that all of their future patients will be assessed according to their unique characteristics and needs. These patients will be able to interact with physicians trained to signal openness and support, establishing a patient-centered dialogue that could positively affect treatment outcomes.

For more information:

Stone, J., Moskowitz, G. B., Zestcott, C. A., & Wolsiefer, K. J. (2020). Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma and Health, 5 (1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000179 (Supplemental)

Jeff Stone, PhD

Jeff Stone, PhD

University of Arizona Distinguished Professor in Psychology and Psychiatry

Director, Self and Attitudes Laboratory

Director, Social Psychology of Sport Laboratory

Research Associate, Arizona Cancer Center (Cancer Prevention and Control)

Jeff Stone, PhD, is a University Distinguished Professor of Psychology in the College of Science, and of Psychiatry in the College of Medicine, at the University of Arizona. He earned his B.A. in Psychology at San Jose State University, his PhD in Psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and completed 4 years of postdoctoral study in the Department of Psychology at Princeton University.

Dr. Stone has devoted most of his career in experimental social psychology to investigating the mechanisms of health attitude and behavior change, and to understanding the role that implicit prejudice and stereotyping plays in the cancer health disparities. Dr. Stone’s currently funded research on cancer health disparities focuses on (1) the implicit biases that providers hold toward stigmatized cancer patients, (2) how implicit biases toward stigmatized cancer patients impacts medical decisions and interactions related to cancer prevention (e.g., smoking cessation), and (3) if having providers complete workshops on the psychology of implicit bias can reduce the effect of implicit bias on the care they provide for cancer patients.